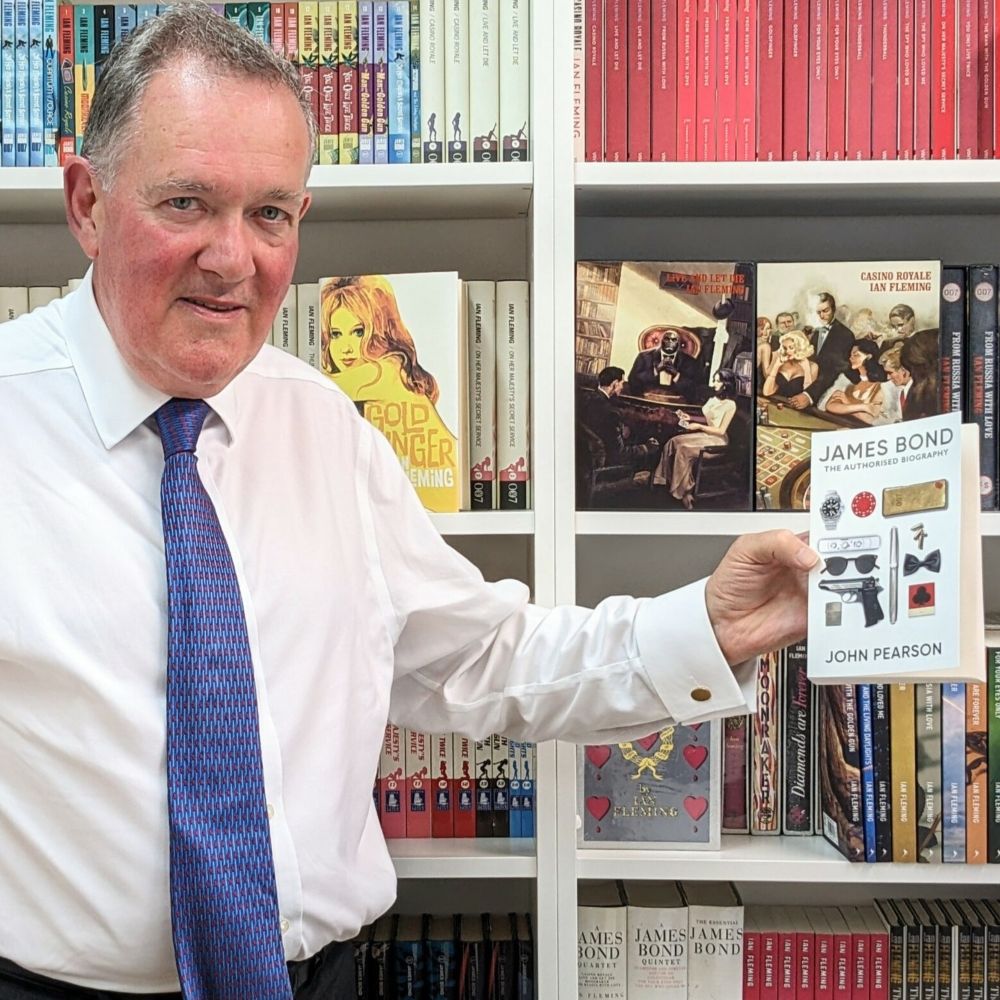

We sit down with the author to talk everything Bond, books and Benson!

What was your introduction to Bond?

I was a child of the 1960s, so I experienced ‘Bondmania’. When Goldfinger the movie opened I was nine years old. I lived next door to two girls and I was playing a game at their house when I heard this music coming from the living room, this fantastic brassy-sounding, dynamic, orchestrated music. I went in and the mom of the two girls was playing the Goldfinger soundtrack. And I kid you not, the woman’s name was M! So I ran home and I told my dad we had to go and see Goldfinger. I just went nuts. I thought it was fantastic. And then I realised there’s all these books. Everywhere you went in those days in 1964 you would see the paperback books by Ian Fleming, the Signet books with the uniformly designed covers. Did you know that that was the first time that an author had a uniformly designed series and paperbacks?

After this initial introduction, how did you become involved with 007?

By the 1970s although I would go to see each movie as it came out, I wasn’t the obsessed Bond fan. I got a degree in theatre as a director. And after I graduated from college, I moved to New York City, and I started directing plays and I also became a musician, composing music for theatrical productions. But then in 1981, the first John Gardner book came out, Licence Renewed. I enjoyed it. I thought, ‘Oh, this is kind of cool’. I got excited again. It was the same kind of excitement that I had in the 1960s. Around this time, some friends and I were sitting around a table when the question came up, if you had to write a book, what would you write? I thought about it, and said, “I’d like to write a big encyclopaedic coffee table book about the history of James Bond.” My friends all thought that was a great idea. One who had just published a book introduced me to his editor and I pitched my idea to her and that became the James Bond Bedside Companion.

In the 1990s I started writing and designing computer games, and that was where I really started honing my fiction. These games were story-based – complicated, elaborate stories where you solve puzzles and you talk to characters. So then in 1995, Peter [Janson-Smith] calls me out of the blue to say that John Gardner doesn’t want to write any more Bond books and would I like to give it a shot? Now, this was something I never campaigned for. Never thought about doing. It wasn’t in my wheelhouse. We talked at length about what my Bond books would be like, and Peter said, why don’t we keep it in sync with the new movies? I agreed but I also wanted to keep Fleming’s Bond. I want him to have all of his vices intact – to be a drinker and a smoker and a womaniser and be more of a brooding, serious guy. He might be a little anachronistic in the ‘90s , but as Judi Dench said in GoldenEye, he’s a ‘misogynistic dinosaur’.

What is your writing process like?

For that first book, I knew if it was published it would be in 1997. And what was the big event for Britain that year? It was the handover of Hong Kong. So I did a little research and once I had a good background on the history of Hong Kong, I wrote an outline for the story. I got the contract, and it was announced I was the next writer – unbelievable . I then travelled to Hong Kong with my wife to do the nitty gritty research. We went to China and Macau, as well as Hong Kong. I travelled in Bond’s footsteps and went to all the locations and met with the Royal Hong Kong Police to talk about Triads. That became the model of all my research trips. I would first look at a world map and pinpoint what hotspots Britain was concerned with and then do a little preliminary research. Then I’d come up with a plot and a story and write the outline, which is the most difficult part of the process. I would spend a month or two on this 20 page treatment broken out into block paragraphs. Each block paragraph represents a chapter – what’s going to happen in that chapter that moves the story forward. I don’t really get into character or dialogue or anything like that. It’s really the plot, the story. Once I work out all the twists and turns and the obstacles and the villains, I really hone it.

My method today is still to write a scene a day. By scene I mean, it has to begin and end. It could be a whole chapter, it could be part of a chapter. It could be two pages, it could be 20 pages. Like Ian Fleming, I would get the first draft completely done in one go, because I think that establishes a pace. Once that’s done, I go back and start reading, revising and deleting.

How did it feel to become a part of the world you had cared about for so long? Did you feel like you’d reverted to nine-year-old Raymond Benson?

Well, when Peter read Zero Minus Ten for the first time, he called me up. It still almost brings tears to my eyes. He just said, ‘Raymond, you’ve written a Bond book.’ Coming from Peter, that was just an incredible feeling. Looking back, who would have thought that nine-year-old Raymond Benson would one day be writing a Bond novel? That was just impossible to even think about. It’s turning a childhood obsession into a career. And those seven years were a roller coaster. I travelled the world. I met all kinds of great people. It was an amazing time.

What have you been doing since your last Bond book?

After Bond I started writing my own stuff. Bond kind of typecast me in the eyes of publishers. But I did not want to write spy novels. I didn’t want to write anything that was like James Bond. My other books are more like Hitchcock stories, you know, normal people in extraordinary circumstances. I also did a lot of what we call tie-in writing. Tom Clancy’s estate hired me to do a couple of books and Metal Gear, the video game. And I was also a sought-after ghostwriter. I’ve been a freelance writer up until now.

How are you feeling about the re-release of Zero Minus Ten? Have you read it back recently?

I’m really excited. I’m so happy about it. During the pandemic I read the books again. I mean, it’s 20/25 years later and they seem very fresh to me. I was reading the detailed things about Hong Kong and the Triads. I was going, wow, these are pretty good .

It’s well documented that From Russia With Love is your favourite Bond book. Do you have a favourite non-Fleming Bond book?

Oh wow. I would have to say one of mine and that would be High Time To Kill. I really think that’s the pinnacle of what I wrote. It’s what I call The Union Trilogy: High Time To Kill, Double Shot and Never Dream of Dying. I think that’s my strongest work. That’s what I liked the most. I would like to shout out to all the authors. It’s not an easy task. I think if you’ve managed to be in the club, to be a Bond author, then more power to you. I consider it a great honour to have these people as my siblings so to speak. I don’t take it for granted. I really appreciate that the Flemings trusted me, that Peter trusted me, and I still love it. I’m still very much a part of it. And I appreciate it.