Writer Tom Cull takes a stroll through London and examines Ian’s career as a journalist, before he found fame with fiction.

On a quiet Sunday in the City of London, I re-traced some of Ian Fleming’s old haunts during his journalism and banking days, including what used to be the Reuters building at The Royal Exchange. It occurred to me that it was here that Ian Fleming got his first taste of writing professionally. Throughout his career, journalism formed an important part of his research and inspiration, before finally becoming a way to remain ‘part of the action’ after the war.

His well-documented two month break in Jamaica to write his James Bond novels was a feat of discipline and economy; writing quickly and accurately and never looking back, trusting totally in his technique. Many writers, including the prolific Raymond Chandler, found this timetable astonishing. He asked Ian in an interview in 1958 how he could write so quickly with all the other things that he did, and remarked that the fastest book he ever wrote was in three months. So, from where did Ian Fleming acquire this skill?

For this we must go back to Monday October 19, 1931.

Fleming was given the responsibility of updating over 500 obituaries, work which his editor-in-chief described as ‘accurate, painstaking and methodical’. But soon, his superiors realised he could be of better use in the field. He was sent to Austria to cover the Alpine Motor Trials (Coupe des Alpes) in the summer of 1932 and thrived on the excitement of it all.

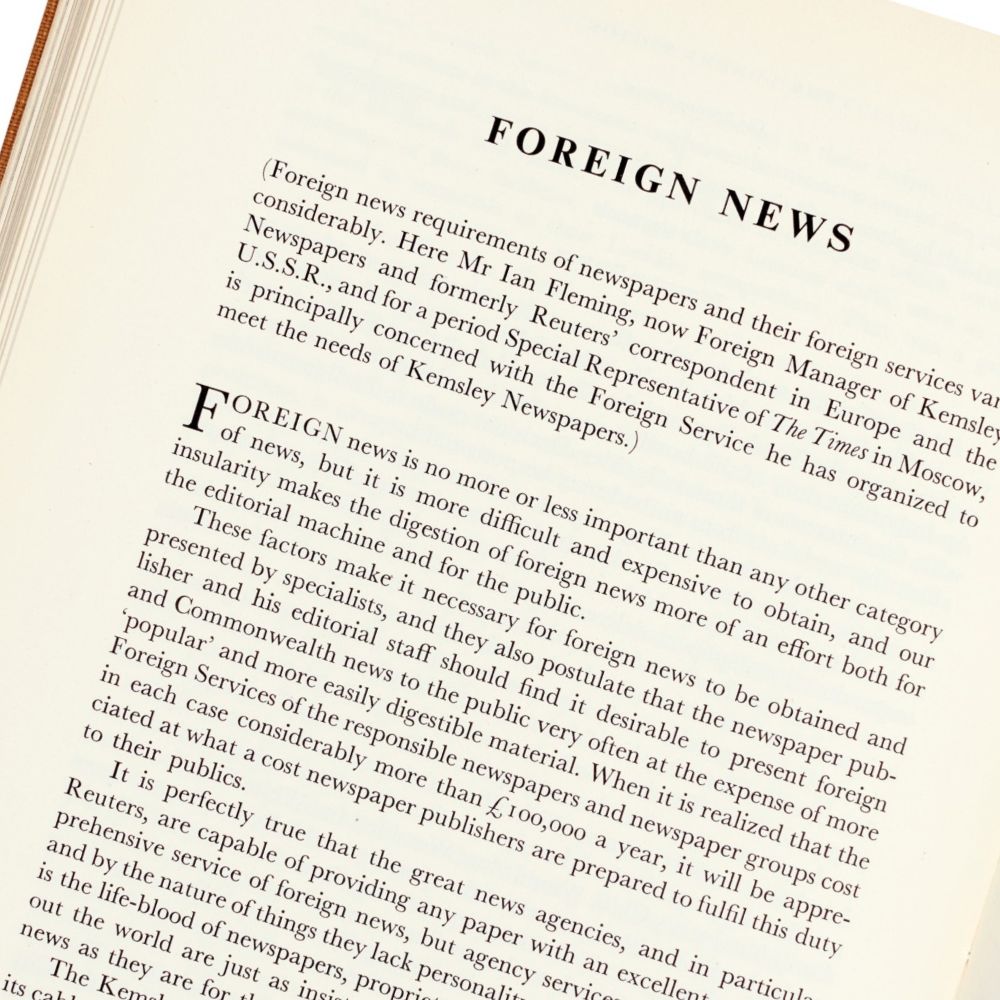

When an intriguing assignment came up in Stalin’s Russia, to report on a court case involving British construction workers (tantamount to a show trial), Fleming was called up. His ‘smattering of Russian’ and the fact that the regular Reuters Moscow correspondent might have had his Russian sources compromised meant that this was Ian’s big break. It was also his first exposure to the dark underbelly of Soviet communism that would pique his interest in cloak and dagger matters and mark Russia out as the political bête noire for the West. His reporting again impressed his peers. He turned in articles on tight deadlines. Ian described his training at Reuters as giving him a ‘good, straightforward style’ and there he learned to write fast and accurately because at Reuters ‘if you weren’t accurate you were fired, and that was the end of that.’

He returned to England to an offer of a higher salary and posting to Shanghai but his earning potential was not quite what he was after. His brother Richard had entered the flourishing family banking firm and it was suggested that Ian had hoped to inherit money from his grandfather, but when this didn’t happen, he decided to go into the City for himself. Doors were being held open for Ian as a fait accompli as he conceded:

‘I loathe the idea from nearly every point of view, and I shall hate leaving Reuters. But I’m afraid it has got to be done.’

In 1933 he was offered a job at the stockbroking firm Cull and Company on Throgmorton Avenue; where he worked for two years before joining Rowe and Pitman, the company from which he was recruited by Naval Intelligence. Fleming’s brief but formative years in journalism would not be his last, as after the war he returned to Fleet Street to work for Kemsley Newspapers as their Foreign Editor, providing him with the perfect opportunity to remain at the heart of things. Another opportunity to hone his craft, collect information, or ‘gen’, and keep his hand in with old contacts from the intelligence world. His friend from SIS days Nicholas Elliott, for instance, kept in touch with Fleming and offered his help if ever he needed a ‘useful piece of information from one of his many City contacts.’

Instead of running agents, Fleming was running foreign correspondents such as Richard ‘Dikko’ Hughes, stationed in Japan, and Anthony Terry who was stationed in Berlin. Two great friends who were to provide him with inspiration and crucial cultural and geographic details for his James Bond adventures You Only Live Twice and The Living Daylights, as well as his non-fiction work Thrilling Cities.

Fleming’s page-turning style owed a debt to those early years at Reuters, which remains to this day one of the largest news organisations in the world.

Tom Cull runs Artistic Licence Renewed. He knew iconic Bond cover artist Richard Chopping well as a child and Tom’s great grandfather hired a young Ian Fleming to work at the family bank Cull & Co. between 1933 and 1935.