Writer Tom Cull explores the real heroes behind some of Ian Fleming’s most admired characters.

Like many authors before him, Fleming took ideas for his James Bond novels from the world around him and the people he knew. The plots were often heightened re-imaginings of his wartime experiences or altered versions of real-world intrigues he’d reported on as a journalist. He often drew upon the names of his real-life acquaintances when christening his characters: from Felix Leiter whose name is inspired by combining the middle name of Fleming’s school friend Ivar Felix Bryce with the surname of their good friends Tommy and Oatsie Leiter, to Mary Trueblood whose name is a nod to Ian Fleming’s secretary at the Sunday Times, Una Trueblood. Many of the female characters in Fleming’s stories have intriguing links to people Fleming knew and many could claim to have been immortalised under the stroke of Fleming’s typewriter keys.

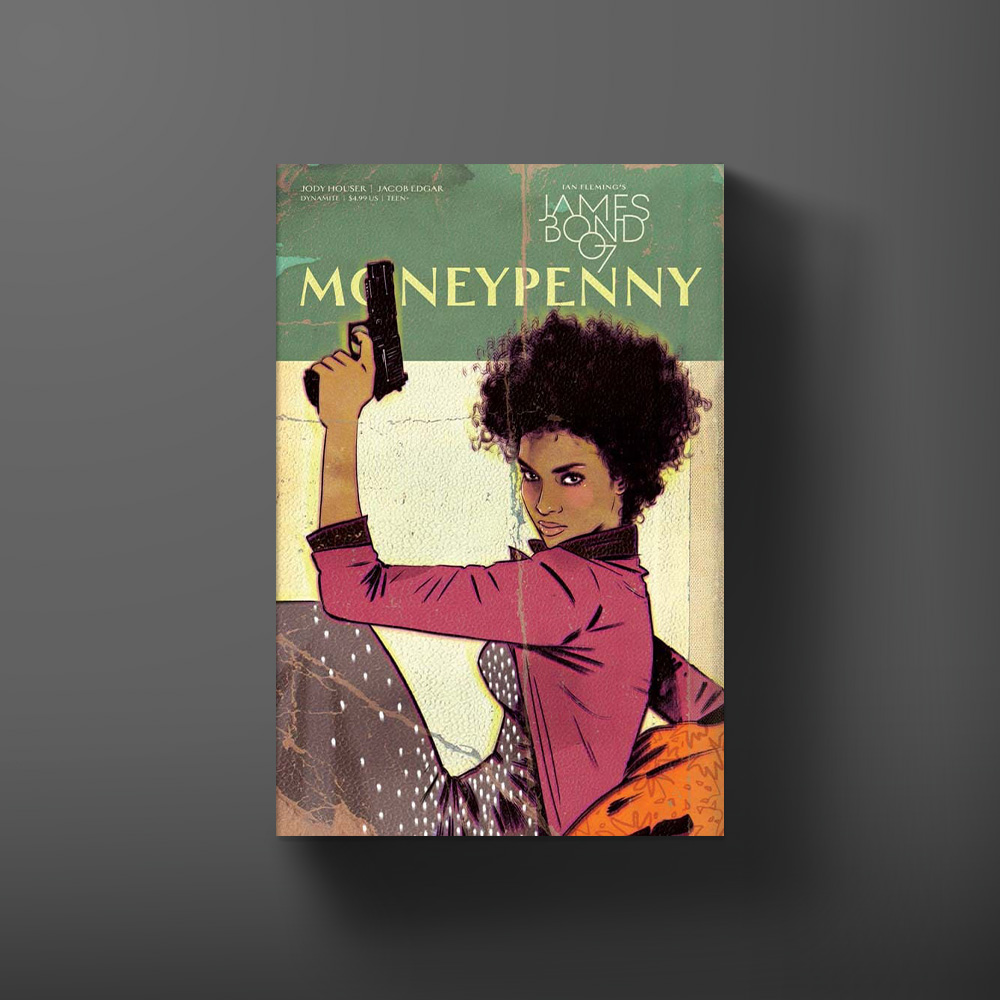

Miss Moneypenny

‘Moneypenny screwed up her nose. ‘But, James, do you really drink and smoke as much as that? It can’t be good for you, you know.’ She looked up at him with motherly eyes.’

Thunderball

As part of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) during the Second World War, Vera Atkins is a strong candidate as an inspiration for Miss Moneypenny. Atkins would visit Room 055a in the Old Admiralty Building down the corridor from Fleming’s office and he would have known of her. She joined Section F (France) in April 1941 and oversaw the secret preparation of more than 400 agents, seeing off most of them in person. Vera was most intimately associated with the female agents whom she called her ‘girls’, among whom were Noor Inayat Khan and Violette Szabo.

Many who worked with Atkins could find her intimidating and protective of her operatives but she commanded the respect of her superiors. The atmosphere at Orchard Court, one of the SOE headquarters, was akin to a private members’ club, with women smoking at their desks and handsome men passing through and breaking into French. They were only known by their aliases.

Another inspiration for Moneypenny is hinted at in an early draft of Casino Royale, where M’s assistant is named Miss ‘Petty’ Pettaval, no doubt borrowed from Kathleen Pettigrew, the Personal Assistant to the Chief of MI6, Stewart Menzies.

Fleming had many loyal secretaries throughout his career and greatly admired their skill and dedication. At The Times, it was Joan Howe who typed the manuscript of Casino Royale. Others who played their part included Beryl Griffie-Williams and Una Trueblood, but perhaps Jean Frampton was the most significant. Letters between Fleming and Frampton appeared in 2008 at Duke’s auctioneers in Dorset. Amy Brenan of Duke’s comments

“You can look on Mrs. Frampton as Ian Fleming’s Miss Moneypenny because he really does seem to rely on her. She was the first person to read the books and the collection is interesting because it details how the James Bond books were put together in the early 1960s.”

Mary Ann Russell

‘Taking these people on all by yourself! – It’s showing off.’

From a View to a Kill

In the short story From a View to a Kill, the character Mary Ann Russell is an agent for Section F who saves Bond’s bacon against the Russian military intelligence agency. Her name is likely to have been inspired by a woman who played a significant role in Fleming’s life, Maud Russell. Her granddaughter Emily Russell has recently edited a revelatory collection of Maud’s war-time diaries, and explains:

‘Maud and Ian met in late 1931 or early 1932 and they quickly became close friends. Through Maud and her husband Gilbert Russell, Ian met a number of influential political figures during the 1930s and also obtained contacts in Military Intelligence. After Gilbert died in May 1942, Ian got Maud a job at the Admiralty. From 1943, she worked in the Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Division (NID) 17Z, a section led by Donald McLachlan that was dedicated to generating white, grey and black propaganda from naval intelligence to undermine enemy morale.’

Maud shared the same zeal for her work at the NID as Fleming did, as she notes in her diary:

‘London, Thursday 10 December 1943 — On Monday the Scharnhorst sinking kept us very busy. Only Mc., C.B. & I. [Ian Fleming] in the room. Then came the news of the sinking of the blockade runner and more excitement. Only Mc. reacts as I do, froths and fizzes over with inward excitement. I. of course is the same as Mc. and I – tension, excitement, hammering energy.GR’

Vesper Lynd

‘”People are islands”’ she said. “They don’t really touch. However close they are, they’re really quite separate.”’

Casino Royale

A popular suggestion for the inspiration behind Vesper Lynd was the SOE agent Krystyna Skarbek, also known as Christine Granville. Polish by birth, she was recruited by the SOE, won a George Medal and was reputedly Churchill’s favourite spy.

Granville was remarkably beautiful and she stole, and broke, many hearts. She was certainly known to Fleming who briefly mentions her in his non-fiction book The Diamond Smugglers. The rumour that Ian Fleming had an affair with Christine Granville is unfounded as her biographer Clare Mulley and writer Jeremy Duns have explored. Christine Granville survived the War but was tragically stabbed by a love-crazed stalker in 1952, aged 44.

There were other members of the SOE who Fleming would have encountered during his time working with Section 17 in Naval Intelligence, where he was responsible for coordinating intelligence between divisions. Violette Szabo was recruited by the SOE at 23, as a war widow with a one year old child. She was dropped into France in 1943 and bravely served the war effort, in one instance fending off an SS Panzer division with a Sten gun before collapsing exhausted. After being captured, Szabo, was shot along with fellow agents Denise Bloch and Lillian Rolfe at the Ravensbrück concentration camp in northern Germany. Szabo’s defiance was greatly admired by her fellow prisoners and she was one of only four women to receive a posthumous George Cross Medal.

Whatever the truth behind the fiction, the women Fleming encountered during his time in Naval Intelligence were truly courageous. They faced daily dangers and risked everything to help secure the freedom of Europe. Fleming was inspired to write about many interesting characters from his real life, from naming Bond’s mother Monique after a former fiancée, to calling Bond’s Secretary Loelia Ponsonby after the Duchess of Westminster. We may never know the full extent of the real people who lend parts of themselves to the James Bond story, but it’s certainly inspiring to learn more about these real-life heroes.

Tom Cull runs Artistic Licence Renewed. He knew iconic Bond cover artist Richard Chopping well as a child and Tom’s great grandfather hired a young Ian Fleming to work at the family bank Cull & Co. between 1933 and 1935.