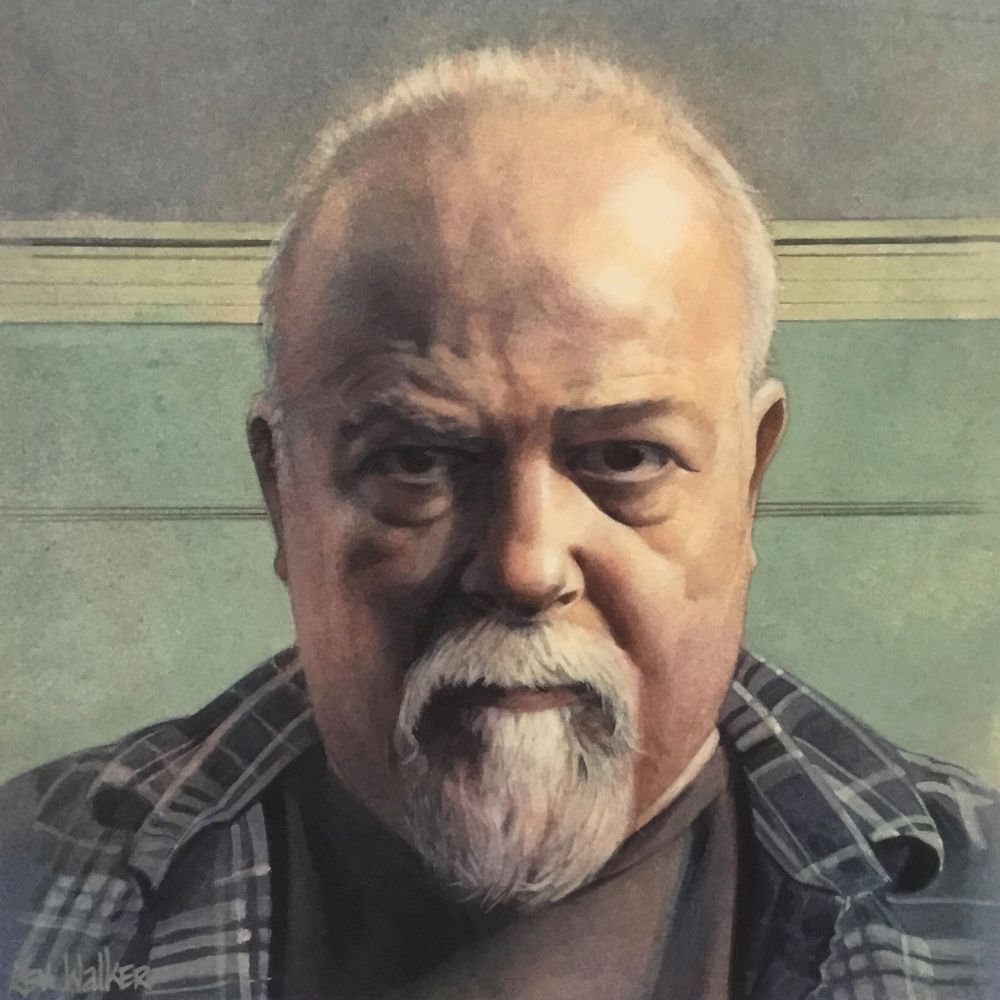

Writer Tom Cull talks about The Man with the Golden Gun, the last of Ian Fleming’s 007 novels.

Eight months after Ian Fleming’s death, The Man with the Golden Gun was published. The birth of the final James Bond novel was difficult and its merits within the canon are still debated among aficionados.

Although Fleming had on many occasions claimed that he was finished with writing Bond books, he had completed the first draft of The Man with the Golden Gun by March 1964. After once again undertaking a Bond novel despite his rapidly deteriorating health, a word to his editor William Plomer at Jonathan Cape, rings with an eerie finality:

‘This is, alas, the last Bond and, again alas, I mean it, for I really have run out of both puff and zest.’

Along with Fleming’s reservations, the artwork for The Man with the Golden Gun also initially proved difficult. Once again Richard Chopping collaborated with Fleming on the dust jacket. Finding Scaramanga’s golden Colt .45 pistol too long to confine to a single panel, his artwork extended to the back of the jacket. Apparently, booksellers were not enamored with the experiment because it required them to open the book in order to display it properly. Now of course, it is regarded as a masterpiece of book jacket design and one of the few still affordable as a first edition.

Fleming’s Gambit

Despite this lack of “puff and zest”, the opening to The Man with the Golden Gun is as good as anything Fleming ever wrote. In summary, the opening is: fantastical, surprising, implausible, and tense. Classic Fleming.

The Service learns that a year after destroying Blofeld’s castle in Japan, Bond suffered a head injury and developed amnesia. Having lived as a Japanese fisherman for several months, Bond traveled to the Soviet Union to learn his true identity. While there, he was brainwashed and assigned to kill M upon returning to England, and during his debriefing interview with M, Bond tries to kill him with a cyanide pistol. Thankfully, the attempt fails.

The psychological tension between Bond and M is palpable in Fleming’s final Bond novel. We know that something’s not right, but we’re not entirely sure what it is until the meeting takes place and we see Bond attempt to assassinate his superior, whom he had previously “loved, honoured and obeyed.” Without question, this unspoken, taut hostility between the two men is only successful because The Man with the Golden Gun explores Bond’s psychology more than any other Bond book.

Spy-thriller writer Charles Cumming, who wrote the introduction to the 2006 Penguin edition of The Man with the Golden Gun, reflected on this opening sequence:

“Given the author’s fragile condition, The Man with the Golden Gun is a remarkable success. The opening sequence is as good as anything Fleming ever received; I particularly love Moneypenny’s ‘quick, emphatic shake of the head’ as she desperately tries to warn Bill Tanner that something is amiss with Bond.”

After recovering from the episode, Bond is dispatched to Jamaica to assassinate Francisco Scaramanga, a.k.a., The Man with the Golden Gun:

“‘Bond was a good agent once,’ said M. ‘There’s no reason why he shouldn’t be a good agent again.’”

The Golden Misfire?

Fleming died before the manuscript could go through the usual process of a second draft and revisions. If Fleming had had his druthers, he might have delayed the publishing of The Man with the Golden Gun, as Fleming biographer Andrew Lycett stated:

“He hoped he might be able to rework it when he was in Jamaica the following spring. But Plomer disabused him of that idea, telling him that the novel was well up to standard.”

Kingsley Amis, a confirmed Fleming fan, was asked for his opinion of the manuscript, but it’s debatable how many of his suggestions, if any, were used. “No decent villain, no decent conspiracy, no branded goods…and even no sex, sadism or snobbery” were just some of Amis’s objections. His main criticisms concerned Scaramanga, whom he labeled a “dandy with a special (and ineffective) gun”. To the celebrated novelist this seemed a bit thin considering Fleming’s usual prowess for creating well-drawn and memorable villains. Amis was also concerned with the lack of what he called ‘The Fleming Sweep,’ Fleming’s signature use of rich detail.

With more hindsight, Amis tempered his earlier criticisms of The Man with the Golden Gun in a later collection of essays entitled What Became of Jane Austen. According to Amis, there is no doubt that the lack of follow-up on plot points, such as why Scaramanga hires Bond as his trigger-man, is due to an uncharacteristically unconfident Fleming. Amis suggests that the Bond-as-trigger-man idea might be the responsibility of “an earlier draft perhaps never committed to paper, wherein Scaramanga’s hiring of Bond is sexually motivated”. Amis goes on to muse that Fleming could have been in critical retreat after too many bashings, and chose not to pursue this idea. However, according to William Plomer in Andrew Lycett’s biography of Fleming, he “can’t think that Ian had any qualms about ‘prudence.’”

Part of Amis’ ire was the result of holding Fleming to such a high standard, and Amis maintained that beneath all the dash and flair (and plot inconsistencies), there was “formidable ingenuity and sheer brainwork” in Fleming. I tend to agree, and if The Man with the Golden Gun were to come out today by a new thriller writer, it would likely receive an overwhelmingly positive reaction. However, in the context of Fleming’s oeuvre and his standing with the critics of his day, The Man with the Golden Gun never stood a chance.

Yet despite all the negative criticism at the time, history has been a little kinder. Of late, The Man with the Golden Gun has undergone critical reappraisal, with acclaimed novelist and Bond continuation author William Boyd arguing for the book as one of Fleming’s “realistic” novels (rather than “fantastical”) in the introduction to the 2012 UK edition published by Vintage.

“Fleming’s Bond novels are full of implausibility and coincidences and convenient plot-twists – narrative coherence, complexity, nuance, surprise and originality were not aspects of the spy novel that Fleming was particularly interested in, and The Man with the Golden Gun is no exception. And indeed Scaramanga’s eventual drawn-out demise is almost low-key, by Fleming’s standards, and as well written – in a brutal, deadpan sense – as anything Fleming achieved.”

Charles Cumming has even better things to say about Scaramanga:

“When 007 and Scaramanga are sizing one another up at the hotel, we are treated to dialogue worthy of Raymond Chandler.”

The Final Curtain

It is apparent that Fleming’s work rate and ingenuity were failing as we witness the end of him and his creation in The Man with the Golden Gun; a novel filled with unintended verisimilitude. After creating and defining a genre, it was mission accomplished for Fleming and Bond well before this novel and Fleming’s old enemy – boredom – was lurking in the wings years before the first sentence of The Man with the Golden Gun had been written.

‘[Bond] decided that he was either too old or too young for the worst torture of all, boredom, and got up and went to the head of the table. He said to Mr. Scaramanga, 2I’ve got a headache. I’m going to bed.”‘

The Man with the Golden Gun is also fittingly about Fleming’s relationship with his beloved Jamaica and the disintegration of British colonialism. Bond and Felix Leiter are awarded the Jamaican Police Medal for “Services to the Independent State of Jamaica”, which is a blunt nod to the end of British imperialism in Jamaica in 1962. In a final effort to hang on to the old vestiges of the British Empire, Fleming takes potshots at the new world power, the United States, and the perceived “Americanization” of the Cold War West. In his recent book Goldeneye: Where Bond Was Born, author Matthew Parker underscores these jabs at America by highlighting how the American-accented Scaramanga is depicted as a keen promoter of tacky Americanized resort hotels with “tropical jungle” dining rooms.

As if he were well aware that he had one figurative bullet left in the chamber, Fleming seized the chance to set the record straight about his creation in The Man with the Golden Gun. Namely, Fleming set out to dispel the notion of Bond as a snob by offering him the ultimate in status symbols – a Knighthood from the Queen. Bond declines, explaining to M: “I am a Scottish peasant and will always feel at home being a Scottish peasant.” One could read this as Fleming’s grand send-off to his critics, or one could see it as Bond’s defiance alone. Either way it presents the literary end for Fleming’s Bond and the very real finale for Fleming himself.

Tom Cull runs Artistic Licence Renewed. He knew iconic Bond cover artist Richard Chopping well as a child and Tom’s great grandfather hired a young Ian Fleming to work at the family bank Cull & Co. between 1933 and 1935.