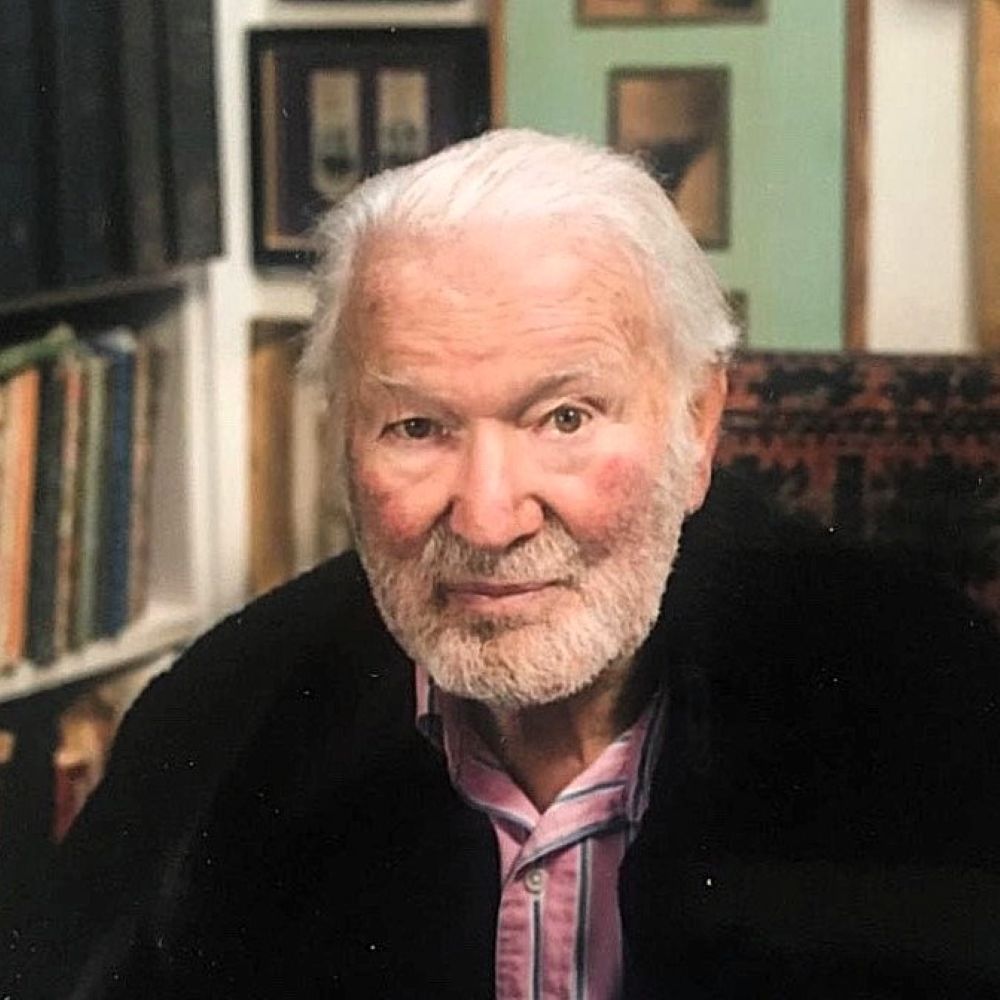

The diaries of Maud Russell, A Constant Heart, shed interesting light on Ian Fleming’s War years. Here Josephine Lane examines their contents and shares insights into this intimate and significant relationship.

On the 8th February 1944, Maud Russell wrote in her diary,

‘Yesterday I. came to dinner, looking well and busy with a dream, the dream being a house and 10 acres on a mountain slope in Jamaica after the war.’

‘I.’ was none other than Ian Fleming, who went on to realise this exotic dream in 1947 by buying an old donkey racetrack in Jamaica where he built GoldenEye, the home which sheltered him from the bitter British winter and where he wrote his James Bond novels every year from 1952 until his death in 1964. Russell’s recently published war diaries reveal that it was her gift of £5,000 that enabled Fleming to build this creative sanctuary which nurtured the rise of his fictional hero. But who was Fleming’s generous benefactor and what significance does their relationship with each other hold?

Born in 1891 to German Jewish parents who had settled in London in the 1880s, Maud Russell was a society hostess and one of the foremost French art collectors of her time. She married Gilbert Russell, a stockbroker and cousin of the Duke of Bedford, during the First World War and they lived between the beautiful Mottisfont Abbey in Hampshire and their house in Cavendish Square in London. Gilbert introduced Maud to many politicians and members of the aristocracy while her interest in the arts encouraged a host of artists, writers, society figures and musicians into their social circle. Amongst them was Ian Fleming who Maud described as having the ‘handsome looks of a fallen angel.’ Although Maud was quite a few years older than Ian, their relationship blossomed from casual acquaintances to intimate friends and likely lovers.

A Constant Heart: The War Diaries of Maud Russell 1938-1945 is skilfully and affectionately edited by Maud’s granddaughter Emily Russell and reveals an intimate portrait of an intelligent and independent-minded woman who was surrounded by influential people of the day. The book is bursting with references to key figures of the time, such as this auspicious entry about a new acquaintance she met when dining with Lord Louis Mountbatten in 1942, ‘At lunch there was his nephew Prince Philip of Greece, a nice looking man, who speaks perfect English and is in the Navy. It struck me afterwards that he would do for Princess Elizabeth.’

Maud’s passion for art led her to be acquainted with several exceptional artists of the day and the diaries record lunches with Matisse, for whom she sat in the 1930s, members of the Bloomsbury Group and the photographer Cecil Beaton. She was also close friends with the artist Boris Anrep who specialised in the art of mosaic and whose work can be seen in the foyer of the National Gallery; a project funded by Maud. Undoubtedly her most important artistic relationship during this period was with Rex Whistler whom Maud commissioned to undertake a stunning and vast trompe l’oeil in what is now known as the Whistler Room at Mottisfont Abbey.

As well as documenting meetings with interesting figures from the 1940s, the diaries open a captivating window into a very unique perspective of life during the Second World War. They are a stark reminder of the great uncertainty and the daily anxiety faced when victory against the Axis powers was by no means guaranteed and international freedom was at grave risk. ‘I was in a rage all day and mad to think we have so miscalculated the German forces as to be in danger of losing Egypt… I roared myself hoarse.’

But few fights were more personal than Maud’s own endeavour to help her Jewish relatives living in Germany. On the 9th–10th November 1938 there was an atrocious, nationwide attack on the Jews in Germany, which came to be known as Kristallnacht – the Night of Broken Glass. Approximately 1,000 synagogues were burned, 7,000 Jewish businesses were destroyed, 91 Jews were murdered and tens of thousands more were arrested and interned in concentration camps. The situation was critical and Maud not only campaigned for visas for her relatives but actually flew to Cologne in December, risking her own safety to help her family. ‘I had arrived on the day when all Jews in Germany were ordered to stay indoors between 8am and 8pm so I wondered whether my appearance might arouse comment, but it didn’t.’ The courage and fearlessness of such actions inspire limitless admiration.

‘I think these months are enormously significant and interesting but I wish I was living on another planet.’

The diaries also bear witness to the death of Maud’s beloved husband Gilbert, who died of asthma in 1942. These passages are incredibly moving, as Maud unravels her grief and processes her loss;

‘The main, the fullest, the richest and the most feeling part of life ended with him. I gave him all the tenderness I possessed. There was little over.’

Reading through the diaries it becomes clear how vital her relationship with Ian Fleming was, particularly during this difficult time, ‘His solid friendship helped me these days. He understood how I felt about G. I think he was very distressed about Gilbert himself.’ Indeed, it is likely that Gilbert Russell engineered Fleming’s role in Naval Intelligence during the War and in turn Ian helped Maud to obtain a post in the Admiralty after Gilbert’s death in her bid to forge a new life.

‘He loves his NID work better than anything he has ever done, I think, except skiing.’

The diaries reveal an intimate closeness and fond affection between Ian and Maud, who meet at least once a week throughout the war. An outcome of this is the extraordinary insight the diaries provide into Fleming’s wartime activities. Amongst other things she notes that Fleming broadcasts directly to the Germans, tours the coastal defences, witnesses the Dieppe raid from a destroyer and visits Spain and Portugal to discuss intelligence matters with Roosevelt’s special envoy. A particularly shocking anecdote is recorded in November 1941,

‘He has been on some dangerous job again. He cannot ever tell me what they are. A house in which he was dining was blown from under him. He and his friends were left marooned on the third floor, the staircase and most of the floors below were blown away. Eventually there was a tap at the window, a fireman’s head appeared and they left the house by the fireman’s ladder. The story was told as if there hadn’t been any danger.’

‘We discussed how either would know if the other was killed. Not knowing at once gives an empty blank feeling.’

There are hints throughout the diaries that Ian and Maud’s relationship was more intimate than mere friendship. Maud provided Ian with his identification tag during the War (which he stipulated be made of gun-metal) and Emily Russell reveals that she found an envelope labelled ‘I.’s’ containing a lock of black hair, amongst her grandmother’s possessions. However, most telling of all is this touching and raw recollection, ‘He talked about marrying me, I had qualities he wants to find. I said, ‘No, ages makes it impossible.’ He said, ‘If I was five years older.’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘If you were at least 10 years older.’ For he is sixteen and a half years younger than me. If he were 10 years older I would marry him, but it’s no use a woman of 52 trying to keep pace with a man of 36. After a few years he might fall in love and want me to release him. I should do it and be alone again after much pain and drama, a good deal older, and in still greater need of compassion. He is very good to me.’

A Constant Heart is a fascinating book, documenting a period of great international importance from a very personal perspective. Maud Russell’s concise and witty records set within an awe-inspiring social circle are a joy to read and her relationship with Ian Fleming is both moving and surprising. Little was known about Maud’s role in Ian’s life before the publication of these diaries and it is a pleasure to encounter Fleming from her perspective as a kind and thoughtful friend. And perhaps her influence runs deeper still. Without her generous gift of £5,000 who knows whether Fleming would have had the peace, quiet and solitude to dedicate himself to devising the deeds of agent 007. But when one learns that he addressed his correspondence to her as ‘Dear M.,’ perhaps it could be argued that her impact was even more fundamental to the literary lore of James Bond.

A Constant Heart: The War Diaries of Maud Russell 1938-1945 is published by Dovecote Press. Photographs courtesy of Dovecote Press and Emily Russell.