Writer Tom Cull talks about Goldfinger, a book full of iconic images, characters and scenes.

It is with little surprise that Anthony Horowitz chose to begin Trigger Mortis just at the point where Bond wraps up the case in Goldfinger. By his own admission, Horowitz has loved this particular Bond novel since childhood.

‘Goldfinger has Bond himself, tired and cynical after a dirty assignment at the start of the book. The sequence at Miami airport as he watches the sun set and considers the vicissitudes of fate is writing of the highest order.’

Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger is perhaps overshadowed in popular culture by the overwhelming success and iconography of the film adaptation. However, it is the novel that provided two of the greatest villains of all time in Auric Goldfinger and his henchman Oddjob, and of course one of the best Bond girls, Pussy Galore, who features in Horowitz’s Trigger Mortis. Perhaps occluded due to Gert Frobe’s excellent performance, is the fact that Auric Goldfinger’s Fort Knox plan speech was taken almost verbatim from the novel.

While her name might have raised eyebrows, Pussy Galore is in more ways than one Bond’s equal rather than a mere gender stereotype. She is a gang leader, a ‘trapeze artiste’. She is also impervious to Bond’s charms, until, as The Moneypenny Diaries author Samantha Weinberg puts it, ‘it suited her.’ Weinberg also noted that another tough woman in Goldfinger, Tilly Masterton, finds ‘her heart beating faster for Pussy Galore than it did for 007.’ These are no pallid damsels in distress.

Whereas many of Fleming’s other novels have an atavistic feel that speaks to the influences of thriller novelists of the early part of the century, Goldfinger is distinctly and unequivocally Fleming. Despite SMERSH’s existence as the omniscient threat in Goldfinger, Fleming is not bound by the Cold War or the Soviet apparatus that he so painstakingly captured in From Russia With Love, his fifth novel. The plot actually takes a back seat in Bond’s Aston Martin DB Mark III, whilst wonderful set pieces take the driver’s seat. Fleming overcomes these plot frailties by delivering memorable scenes with glorious self-indulgence and glee. Even with no hitherto interest in golf, readers cannot help but be enthralled by the gamesmanship between Bond and Goldfinger at the Royal St. Marks course.

‘As soon as Bond had hit the shot he knew it wouldn’t do. The difference between a good golf shot and a bad one is the same as the difference between a beautiful and a plain woman – a matter of millimetres.’

It is perhaps no accident that the novel is best remembered for its individual scenes, since many were ideas that Fleming had originally conceived as short stories and plot devices for other project. Since many of them did make it into the novel, Goldfinger is one of Fleming’s longest endeavours, and as often is the case, Fleming drew on personal experiences in order to create these timeless characters and events. The modernist architect Erno Goldfinger, whose buildings Fleming abhorred, lent his name to Auric Goldfinger. Alfred Whiting, the golf pro at Fleming’s beloved Royal St. George’s golf course, became Alfred Blacking, a Royal St. Marks caddy. As in Moonraker, Fleming’s familiar setting of Kent is the backdrop, for Bond’s early encounters with Goldfinger. Yet whereas Moonraker lacks some international glamour, Fleming made up for this deficiency in Goldfinger by staging the action in a number of exotic and unfamiliar locations including Miami, Geneva, and Kentucky.

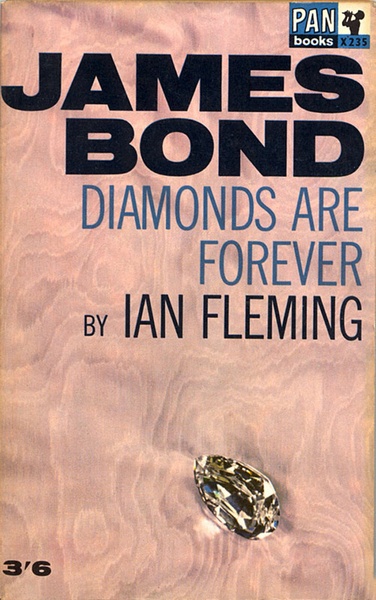

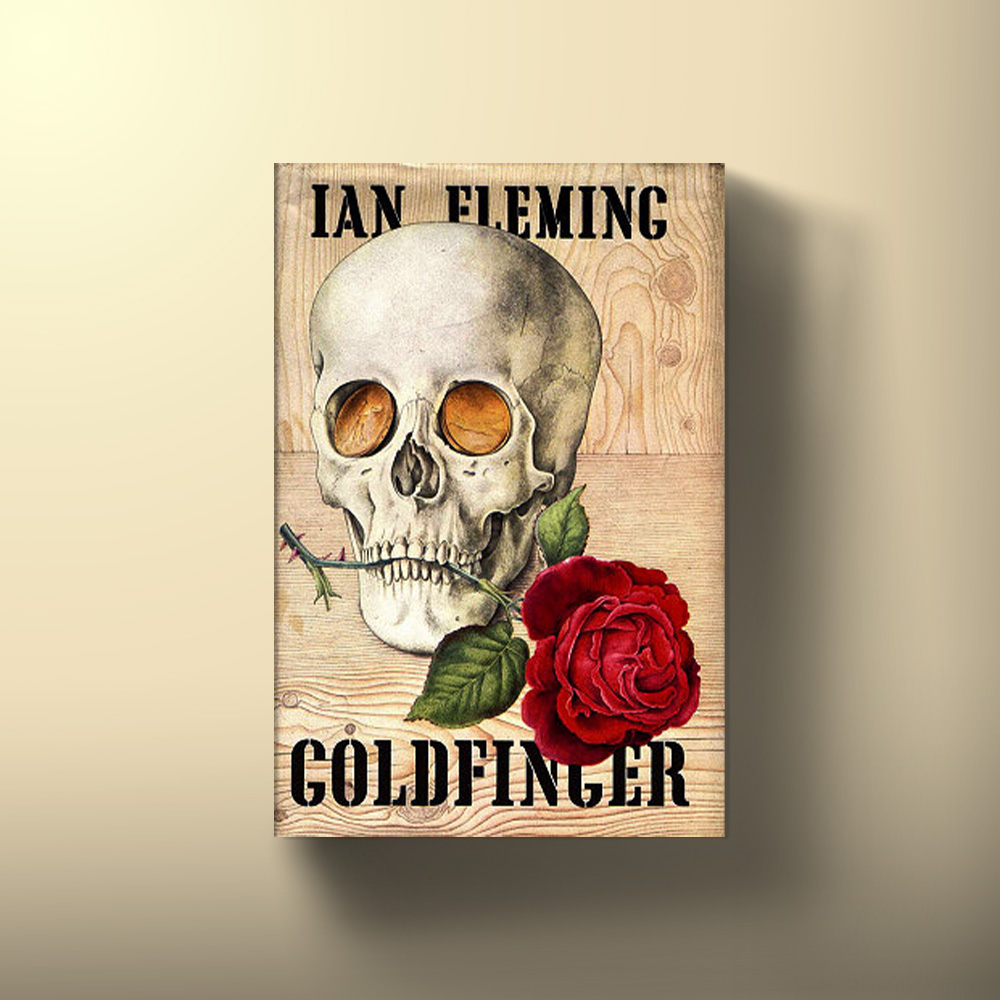

Goldfinger, published on 23 March 1959, was Ian Fleming’s 7th James Bond novel and was a great success which hit the top of the best-seller list almost immediately. Fleming was clearly proud of this effort and took on various promotional activities in order to show it off. The book also came complete with another outstanding Richard Chopping dust jacket cover, this one showing a skull with gold coins for eyes biting a rose. Chopping himself considered this piece to be his finest work in the series.

Critically, Goldfinger was better received than some of Fleming’s previous efforts. Even Anthony Boucher of The New York Times, who was Fleming’s arch-nemesis and a constant critic of James Bond, said ‘the whole preposterous fantasy strikes me as highly entertaining.’ In his 99 Novels: The Best in English Since 1939, Anthony Burgess perhaps unexpectedly selected Goldfinger as one of his honoured entrants, while O.F. Snelling, a friend of Fleming and the author of Double O Seven James Bond: A Report, perhaps puts it best when he writes that,

‘Ian Fleming walked an extremely shaky tight-rope across a pond of very thin ice when he wrote Goldfinger. What with its characters and situations, Goldfinger is the most bizarre example in a generally somewhat extraordinary output. But it is also, I submit, at the same time one of the best.’

Goldfinger sees Ian Fleming and his most famous creation at the height of their powers. Upon publication, the book also provided a welcome sense of escapism during a particularly tense portion of the Cold War. Take the time to relive Bond’s classic adventure.

Tom Cull runs Artistic Licence Renewed. He knew iconic Bond cover artist Richard Chopping well as a child and Tom’s great grandfather hired a young Ian Fleming to work at the family bank Cull & Co. between 1933 and 1935.