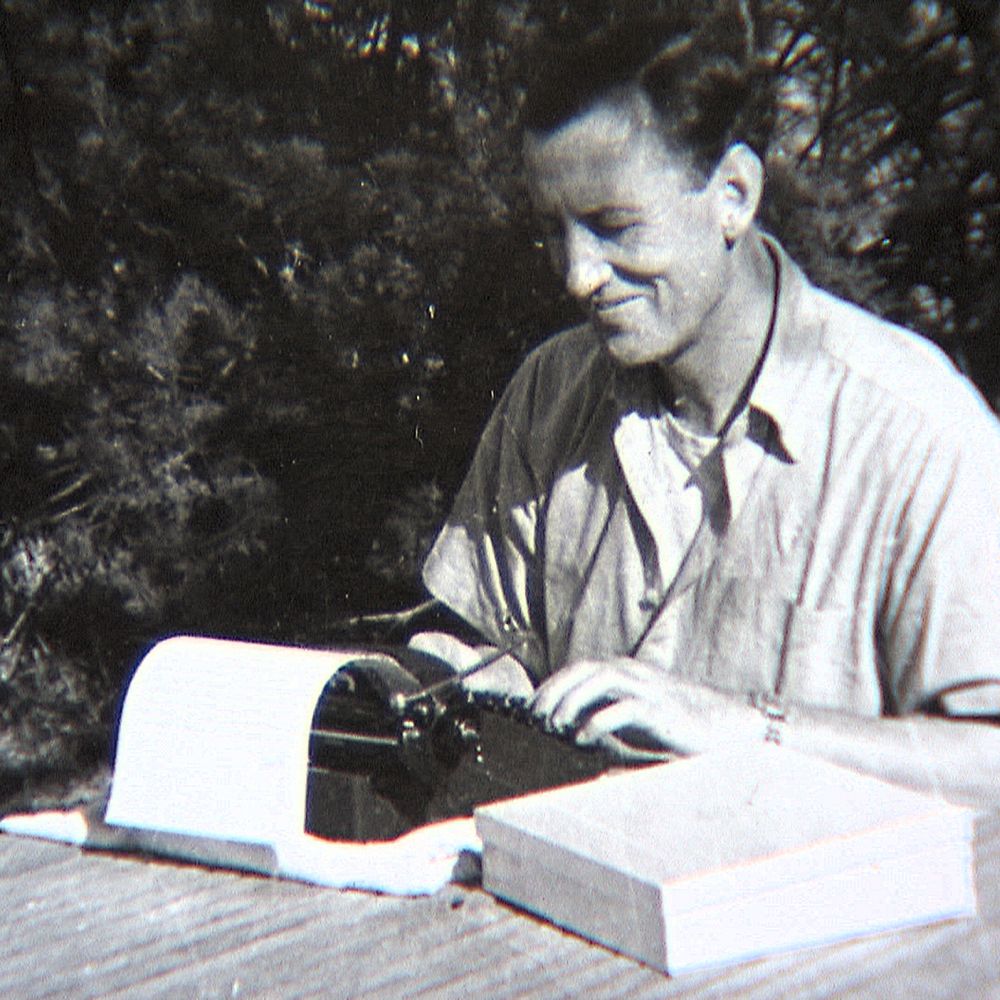

Writer Benjamin Welton looks back at Ian Fleming’s war years and how they influenced his literary creativity.

James Bond remains the quintessential cold warrior of fiction, and yet it’s not that conflict that animated his creator. Sure, the Soviet Union and her agents are the arch villains of Fleming’s oeuvre, and the mere existence of SMERSH (a real entity of history) is evidence enough of Fleming’s interest in using Bond as a loyal British ‘instrument’ in the service against a contemporary enemy. But despite Fleming’s journalistic attachment to current events, the engine driving his creation of Bond was World War II.

Described by Fleming once as a ‘very interesting war,’ the Second World War gave this former Etonian and child of privilege not only an insider’s view of intelligence work and covert operations, but also a deep sense of duty that he later bequeathed to 007. As a result, Fleming’s Bond novels are haunted by the specter of the 1939-1945 conflict, from the machinations of diehard Nazis like Sir Hugo Drax or former double agents like Ernst Stavro Blofeld to Bond’s overall excitement for what American President Theodore Roosevelt once called ‘the strenuous life,’ albeit one chock full of custom-made cigarettes, well mixed drinks, and beautiful, but slightly damaged women.

Salad Days

The military and the call to defend the crown were never far from young Fleming. His father, Valentine Fleming, had served first as a Conservative MP before being killed on the Western Front in 1917. The death of his father left a giant vacancy in the Fleming household, and his mother Evelyn pushed her sons to pick up the mantle left behind by their father. Fleming’s older brother Peter became not only an Oxford-educated adventurer and travel writer, but he also served as an officer in charge of military deception during World War II in Southeast Asia.

It took longer for such glory to come Ian’s way. After attending Eton College, where he collected an impressive array of sporting titles and trophies, Fleming was pushed by a disapproving housemaster at Eton and his mother to attend the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. While there less than a year, Fleming flaunted a good many of the school’s strict regulations and left after an indiscretion out in town.

After failing to achieve a commission, Fleming spent the interwar years performing an assortment of high-end jobs. Besides trying his hand at banking with Cull & Co. and being a stockbroker with Rowe and Pitman, Fleming’s most important role before becoming a novelist was his time as a journalist and sub-editor for Reuters. Although Fleming’s mother had lobbied for the job on behalf of her wayward son, Fleming proved to be an excellent journalist, which Anthony Burgess, in a preface to the 1987 Coronet paperback editions of Ian Fleming’s original Bond novels, blames for Fleming’s ‘clarity of…style’ :

‘It is important to remember, that, like Daniel Defoe, [Fleming] was a journalist before he was a writer of fiction, and a good journalist too. The clarity of his style in the novels proclaims this, the apt image, the eye for detail, the interest in world affairs on the one hand and, on the other, the fascination with the minutiae of everyday life.’

While on assignment for Reuters in 1933, Fleming covered the trial of six British engineers with Metropolitan-Vickers who were accused of espionage and sabotage while working in the Soviet Union. The trial was nothing more than a Stalinist show trial, but it did provide Fleming, who had only been with Reuters for eighteen months at that point, with a taste of the world of international espionage. While not his first taste (Fleming had earlier attended a private school in Austria run by a former British secret agent named Ernan Forbes Dennis), the Metropolitan-Vickers trial did however expose Fleming to the dangers of communism and the potential thrills associated with being a British spy abroad.

On His Majesty’s Secret Service

Later in life, Fleming admitted that: ‘I extracted the Bond plots from my wartime memories, dolled them up, attached a hero, a villain, and there was the book.’ Barring some exaggeration, Fleming could lay claim to being privy to some of the war’s more interesting elements. As a Royal Navy Commander attached to Senior Service, Fleming got to experience the ‘intelligence machine’ from the inside. While serving as a liaison between MI5, the Security Service, and SOE, Fleming regularly attended top secret meetings and had access to Bletchley Park, where men like Alan Turing and others were busy decoding the ciphers of the German Enigma machine.

Fleming wasn’t content to just spend the war as a go-between, however. As author Nicholas Rankin details in his excellent book Ian Fleming’s Commandos, Commander Fleming was instrumental in the creation of a commando force within the Naval Intelligence Division, which he labeled an ‘Intelligence Assault Unit.’ Called both 30 Commando and 30 Assault Unit, this collection of Naval intelligence officers and Royal Marine Commandos were tasked with ‘pinching’ secret material from the enemy. Along the way, 30AU saw action in Algeria, Norway, the Greek Islands, Sicily, and most disastrously of all, the assault on Dieppe.

While Fleming was not frequently on the front lines, he did however actively engage in overseeing the unit’s activities (he was also known to accompany them on certain assaults), plus he had a habit of concocting fabulous missions for his men. Examples include Operation Ruthless, which was a plan devised before the creation of 30AU in order to retrieve the Enigma codebooks while using what Fleming himself described as ‘a tough bachelor, able to swim.’ Operation Ruthless’s ideal operator not only prefigures James Bond’s grueling underwater storming of Mr. Big’s fortress in Jamaica in Live and Let Die, but Fleming’s description of the task reads like a synopsis of one of Bond’s many exploits:

TOP SECRET

For Your Eyes Only. 12 September 1940

To: Director Naval Intelligence

From: Ian Fleming

Operation Ruthless

I suggest we obtain the loot by the following means:

Obtain from Air Ministry an air-worthy German bomber

Pick a tough crew of five, including a pilot, W/T operator and word-perfect German speaker. Dress them in German Air Force uniform, add blood and bandages to suit

Crash plane in the Channel after making SOS to rescue service

Once aboard rescue boat, shoot German crew, dump overboard, bring rescue boat back to English port

Another Fleming-created operation was Operation Golden Eye, which centered on keeping the lines of communication open to Gibraltar if Spain decided to join the Axis. Like Operation Ruthless, Operation Golden Eye was closed down before it could be put into action.

The War Becomes a Best-Seller

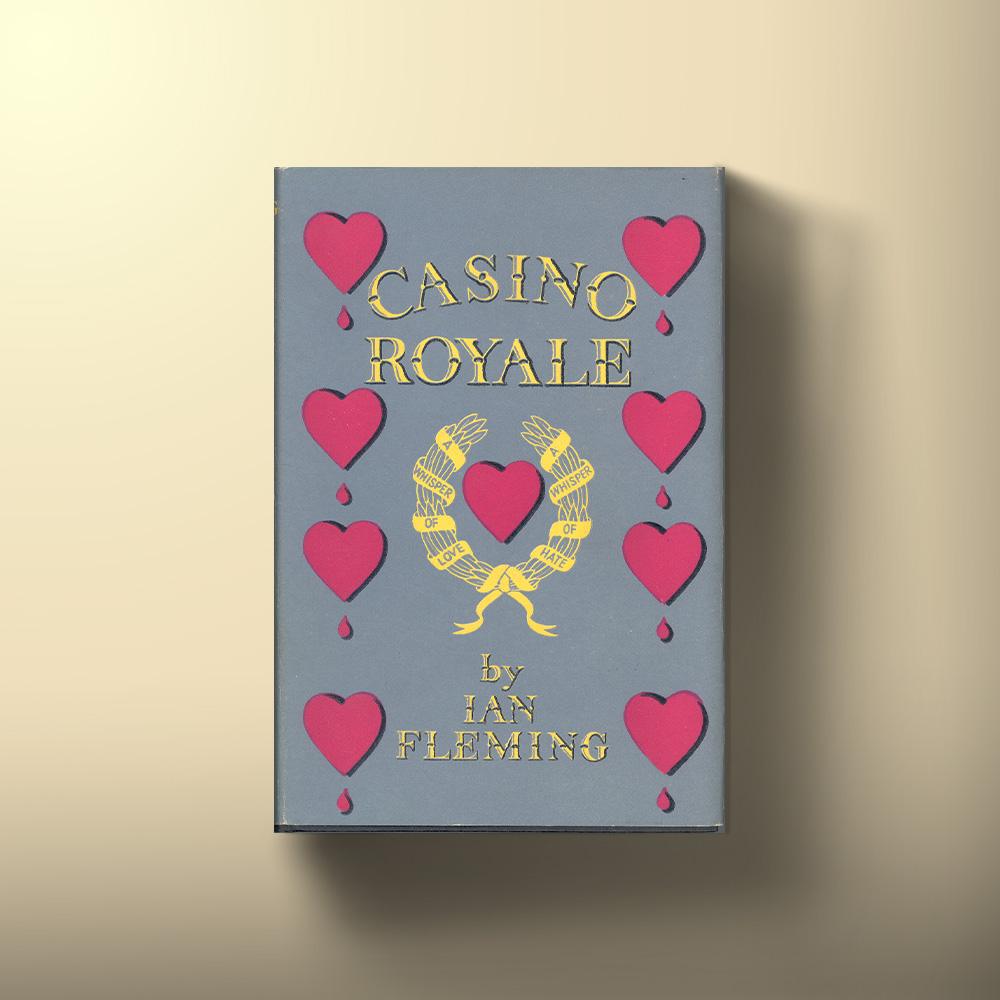

When Fleming set out to write Casino Royale, the ‘hot war’ had turned cold. Britain’s main enemies were communism and the various post-colonial nationalist movements that helped to bring down the empire. And yet, in most of Fleming’s Bond novels, the action as well as the villains all have some tie to the older conflict. Moonraker deals not only with the lingering fear of the Nazis’s V-2 rocket, but also the idea that some former Nazi scientists in Britain and America were still enraptured by the Hitlerian philosophy. According to Ben Macintyre’s For Your Eyes Only: Ian Fleming and James Bond, the inspiration behind mining Mr. Big’s boat in Live and Let Die and giving the Disco Volante a trap door in Thunderball may very well have been the 10th Light Flotilla, a special unit of the Italian Navy that Fleming saw operate in the Mediterranean during the war. Of course, Bond’s most enduring enemy, Blofeld, began his life of infamy as a Polish double agent who sent secret items to the Nazis ahead of their 1939 invasion of Poland.

Even Bond himself is a product of the war, for while serving as Commander Bond in the Royal Navy’s Intelligence Service, he earned his 007 title by killing what he describes in Casino Royale as ‘two villains’ — a Japanese cipher expert and a Norwegian double agent. And while Bond spends a small portion of the same novel conflicted over his role in the more morally slippery Cold War, he nevertheless decides to stay in the action as an agent tasked with eliminating or weakening some of the wrongs associated with the postwar fallout between the former Allies. In another way, the Bond novels can be read as a continuation of Fleming’s work during the war, as Bond, through fiction, reasserts British dominance on the world stage all the while re-living some of his creator’s experiences from his time as an intelligence officer.

Benjamin is a freelance journalist who has been published in The Atlantic, VICE, MI6-HQ, and others. He is a regular contributor to Literary007.com.