‘”There’s a big packet of smuggled stones in London at this very moment”, said M, and his eyes glittered across the desk at Bond’

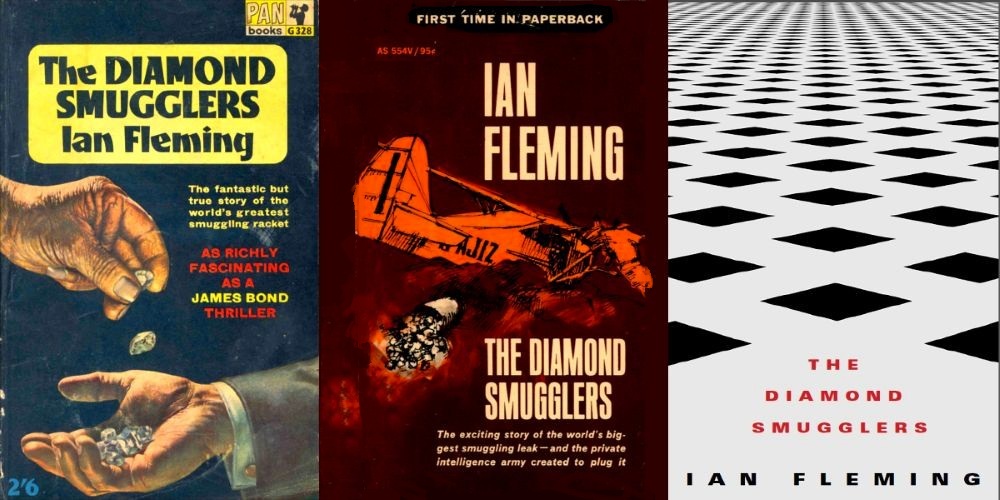

On 15th September 1957, Ian Fleming’s true account of diamond smuggling in Africa was serialised by the Sunday Times. The articles were then bound together and published as a book the following year. Sixty years on, we celebrate this fascinating piece of journalism which shows a side to Fleming’s writing career not often in the spotlight.

After a period studying in Europe, Fleming became a journalist in the 1930s for Reuters News Agency and covered stories such as the Metro-Vickers espionage trial in Moscow. After trying his hand at stockbroking and then working in Naval Intelligence during the Second World War, Fleming returned to journalism and became Foreign Manager at Kemsley News, owners of the Sunday Times. Fleming’s experience in journalism helped him to hone a quick and engaging writing formula which shaped his style as a thriller writer.

Fleming first read a story about illicit diamonds leaving Sierra Leone in the Sunday Times in 1954. The article intrigued him and he was inspired to research it for the basis of one of his James Bond stories. Diamonds Are Forever was published in 1956 and the following year, Fleming was invited to write an account of the experiences of a real-life diamond spy, resulting in The Diamond Smugglers.

Here, Fergus Fleming, writer and Ian Fleming’s nephew, takes us behind the book.

When The Diamond Smugglers was first published Ian Fleming had a copy bound for his own library. On the flyleaf, as was his custom, he wrote a short paragraph describing its genesis. It started with the alarming words: “This was written in two weeks in Tangiers, April 1957.” As the ensuing tale of woe made clear, he didn’t consider it his finest fortnight. He ended with the dismissive verdict: “It is adequate journalism but a poor book and necessarily rather ‘contrived’ though the facts are true.”

It should have been a golden opportunity. The Sunday Times had acquired a manuscript from an ex-MI5 agent called John Collard who had been employed by De Beers to break a diamond smuggling ring. Fleming, whose Diamonds Are Forever had been one of the hits of 1956, was invited to bring it to life. Treasure, travel, cunning and criminality: here were the things he loved. Flying to Tangier – home to every shade of murky dealing – he spent ten days interviewing Collard, for whom he had already prepared the romantic pseudonym “John Blaize” and the equally romanticised job description of ‘diamond spy’.

The glister tarnished swiftly. He visited neither the diamond fields of Namibia or Sierra Leone, with which the story was primarily concerned, but sat in the Hotel Minzah typing up his notes. It rained constantly and he found the landscape dull. There was little scope for literary flair, his more extravagant flourishes being blue-pencilled routinely by Collard. When the final version was serialised by the Sunday Times in September and October 1957 further material had to be excised under threat of legal action by De Beers. “It was a good story until all the possible libel was cut out,” Fleming wrote gloomily.

Yet if The Diamond Smugglers was a disappointment to its author it still contains flashes of Fleming-esque magic. Amidst the Tangerian alleys he strays unerringly to the thieves’ kitchen of Socco Chico, “[where] crooks and smugglers and dope pedlars congregate, and a pretty villainous gang they are.” Travelling with ‘Blaize’ to the Atlantic coast, he encounters a forest of radio masts – still one of the world’s communication hubs – where they “could imagine the air above us filled with whispering voices.”

Later, as they walk down the beach they stumble (literally) on a shoal of Portuguese Men of War driven ashore by a storm. Alone on the tip of Africa, with the coast stretching 200 miles to Casablanca, the sea running uninterrupted to America, and a carpet of jellyfish beneath their feet, the two men conduct what has to be one of the most surreal interviews in history. “It amused Blaize to stamp on their poisonous-looking violet bladders as we went along,” Fleming wrote, “and his talk was punctuated with what sounded like small-calibre revolver shots.”

Today The Diamond Smugglers is one of Fleming’s least known works. But in its time it was one of his most commercially valuable. It sold in its hundreds of thousands. No sooner was it in print than Rank bought a film treatment for the princely sum of £12,500. (Further misery: he had to split the proceeds with Collard and the Sunday Times.) Nothing came of the project. But in 1965, by which time Fleming was dead and Bond a worldwide phenomenon, it flared briefly into life. Items concerning its progress featured in the press: a thrusting young producer had it in hand; John Blaize would emerge as a new Bond-like character; Kingsley Amis had been hired to write the script; the drama would be intense. After a while the announcements became slightly plaintive. And then they stopped.

More than forty years later it remains something of a conundrum; a journalistic chore that its author disliked but which nevertheless became a best-seller and very nearly his first film; a book that is neither travelogue nor thriller but combines the discarded hopes of both; a tale of international intrigue and exploding jellyfish that leads to the final question: “Who wouldn’t rather play golf?”

It is a wry, unplaceable thing, but all the more interesting for that. Certainly it doesn’t live up to Fleming’s self-damning critique. Take this sentence from the opening paragraph:

“One day in April 1957 I had just answered a letter from an expert in unarmed combat writing from a cover address in Mexico City, and I was thanking a fan in Chile, when my telephone rang.”

If you’re given a line like that you can only read on.

Fergus Fleming is the author of The Man with the Golden Typewriter: Ian Fleming’s James Bond Letters.